The NIH Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) presented on the psychology of career decision making at the 13th Annual NIH Career Symposium.

By Brittany Fleming, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Fellow in the Salmonella Host Cell Interactions Section of the Laboratory of Bacteriology at Rocky Mountain Laboratories.

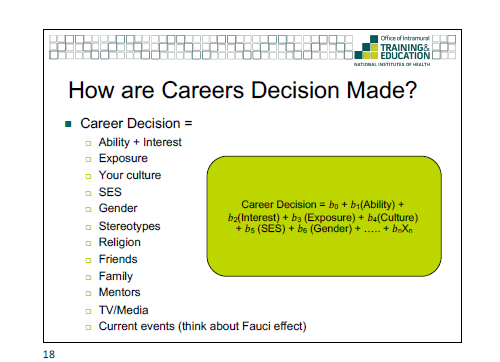

We often believe that having more choices creates better outcomes—but in reality too many options can lead to choice overload and a sense of decision paralysis. This so-called “paradox of choice” was presented to NIH predocs and postdocs on the very first day of the NIH Career Symposium in May, a timely choice as they embarked on a week-long journey exploring the many careers available to fellows. “The Psychology of Career Decision Making,” presented by the NIH Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) senior advisor for social and behavioral sciences Anna Han, Ph.D., and NIH career and wellness advisor Denise Saunders, Ph.D. Anna’s portion dealt with the surprising factors that influence our career decisions and tips on how to make them, and Denise focused on the process involved in making these important decisions.

Anna explained that the more choice we have, the higher our expectations—sometimes leading to disappointment. The more complex our decision is—like deciding our future—the more likely we are to experience overload. When we’re caught in the paradox of choice, we either avoid our decision or further delay it by staying in school or continuing with our fellowships, or we select the default by continuing to follow the expected path we falsely believe applies to us, without exploring any other potential futures at all.

The best way to avoid the phenomenon of choice overload and the ultimate feeling of buyer’s remorse is “to be open-minded at first,” emphasized Anna, but quickly narrow down our possible career decisions. Before we do that, Denise explained, we need to know ourselves and know our options. Take time to clarify our intent, our values, and our skills, and take into consideration any familial, financial, geographical, and cultural ties that may impact our career choice. Understanding our options through research, networking, and informational interviews can help build a strong base of knowledge that we can feel confident in to make complex life decisions. As simple as this all sounds, challenges arise that stop us from engaging in the process—the fear of making the wrong choice, the obsession with making the perfect choice (“there actually is no such thing,” said Denise), or overanalyzing ourselves and our options and other elements that may be out of our control.

If you are like me, a postdoc or a graduate student trying to figure out my next steps after my time at NIH and feeling completely overwhelmed by all the possible choices, this talk will help to normalize your anxieties and help orient you to make those career decisions.

A recording of this talk and many other OITE events can be found on OITE’s YouTube channel: The Psychology of Career Decision Making. For more information about OITE’s Mental Health and Well-Being of Biomedical Researchers series visit their the OITE website.