Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a common virus that causes mononucleosis, or mono for short, and is associated with some types of cancer and autoimmune diseases. Despite EBV’s known effects and potential to cause disease, there are few therapeutic options and no licensed vaccines targeting the virus. Looking for ways to counter EBV, NIAID researchers are examining how the virus recognizes and interacts with cells at the molecular level. New research published in Immunity reveals the high-resolution crystal structure of a protein on the surface of EBV in complex with the receptor it binds to on the surface of human immune cells, called B cells. The researchers also discovered antibodies that potently neutralize EBV and found that they recognize the viral surface protein using interactions similar to those between EBV and its receptor on host cells. This research identifies a vulnerable site on EBV that could lead to the design of much-needed interventions against the virus.

EBV, also known as human herpesvirus 4, is one of the most common human viruses—nine out of ten people have or will have EBV in their lifetime. After being infected with EBV, many people experience no symptoms, but some experience symptoms of mononucleosis, such as fever, sore throat and fatigue. These symptoms are often mild but can be more severe in teens or adults. After the early stages of infection, the virus hides in the body and can emerge later in life or when the immune system is weakened. Recent studies have also found that EBV is linked to several types of cancer, autoimmune diseases including lupus, and other disorders.

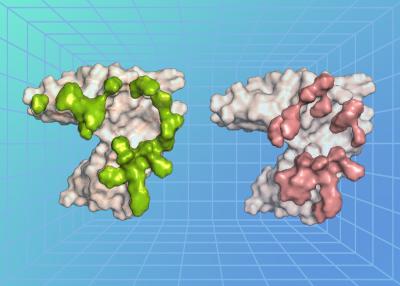

A key step in EBV infection is for the virus to enter a cell in the body, which begins with the virus binding to a protein on the cell’s surface. The researchers, led by Dr. Masaru Kanekiyo, chief of the Molecular Immunoengineering Section at NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center, examined the atomic-level structure of an EBV surface protein called gp350 when bound to a protein on the surface of B cells called complement receptor type 2 (CR2). Usually, CR2 binds to a protein fragment, or ligand, called complement component C3d as a part of the immune response following a viral infection. The researchers found that the EBV protein precisely bound to the cell surface protein CR2 at the region where its natural ligand C3d binds, revealing that there is structural similarity between EBV and C3d in recognizing CR2 and how the virus exploits this interaction to enter and infect a cell.

The researchers also isolated neutralizing antibodies (nAbs)—immune proteins that neutralize EBV—from animals immunized against EBV and EBV-infected people. They found that the antibodies neutralized the virus in laboratory tests by binding to the EBV gp350 protein. They further determined the atomic-level structure of three of the nAbs when bound to EBV gp350. All three nAbs bound to gp350 at the same region of the protein—the region where it also binds to the cell protein CR2, demonstrating that this binding site is an important target on the virus for neutralization.

The way the CR2 cell surface protein binds its natural ligand C3d can be likened to a key fitting a lock. In this case, the key is a negatively charged pocket on the surface of C3d, while the lock is an arrangement of positively charged arginine residues on the surface of CR2. The researchers observed a remarkable molecular mimicry that occurred in duplicate. On one side, EBV gp350 mimics the characteristics of C3d, pretending to be the natural key that fits CR2 on the cell surface, unlocking the cell for the virus to infect it. On the other side, the anti-EBV nAbs mimic CR2, where they act as a lock to block the EBV gp350 protein from binding to a cell for the virus to infect. The mimicry existing on both sides of this lock-and-key set indicates that this interaction is an important step for EBV infection—and represents a major point of viral vulnerability, according to the researchers.

The findings define critical molecular interactions between EBV and its host cells. The researchers noted that more work is needed to apply these findings to the development of interventions, including examining whether the newly discovered nAbs can provide protection from EBV infection in animal models and people. This research may reveal new avenues to treat and prevent disease caused by this widespread pathogen.

Reference:

- M Gorden Joyce. Structural basis for complement receptor engagement and virus neutralization through Epstein-Barr virus gp350. Immunology [10.1016/j.immuni.2025.01.010] (2025).